The History of the Berlin Wall and Its Symbolism During the Cold War

The Berlin Wall, a grim symbol of the Cold War, remains one of history’s most potent and enduring images. More than just a physical barrier dividing a city, it represented the ideological chasm between the Soviet Union and the Western world, embodying the stark contrast between communism and capitalism, and serving as a chilling testament to the geopolitical divisions that fractured Europe for decades. This essay will delve into the intricate history of the Berlin Wall, exploring its construction, its symbolism during the Cold War, its impact on the lives of Berliners, its eventual fall, and its lasting legacy in the twenty-first century.

The Genesis of Division: Post-War Berlin and the Seeds of the Wall

The story of the Berlin Wall is intrinsically linked to the aftermath of World War II and the subsequent division of Germany. After the Allied victory, Berlin, located deep within Soviet-occupied East Germany, was itself divided into four sectors: American, British, French, and Soviet. This arrangement, a precarious balance of power, quickly deteriorated as the Cold War intensified. The emerging ideological conflict between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union manifested itself in Berlin, transforming the city into a microcosm of the global struggle.

The initial post-war years witnessed a significant migration of East Germans to the West, driven by the stark economic and political disparities between the two German states. West Germany, supported by the Marshall Plan and embracing a capitalist system, experienced significant economic growth and offered a stark contrast to the centrally planned, economically stagnant East Germany under Soviet control. This “brain drain” from East to West posed a serious threat to the communist regime in East Germany, undermining its legitimacy and draining its skilled workforce. Berlin, with its relatively open borders compared to the rest of the Inner German border, became the primary escape route for East Germans seeking a better life.

The sheer number of people fleeing East Germany through Berlin was staggering. Between 1949 and 1961, over 2.5 million East Germans, representing a significant portion of the population, successfully crossed over to West Berlin and West Germany. This mass exodus, seen as a direct challenge to the East German regime’s authority and a significant blow to the Soviet Union’s influence, necessitated a drastic response. The solution, ultimately, was the Berlin Wall.

The Night the Wall Rose: Construction and Immediate Consequences

The decision to construct the Berlin Wall was made in secrecy, reflecting the totalitarian nature of the East German regime and its dependence on Soviet backing. On the night of August 13, 1961, under the cover of darkness, East German border guards, supported by the Soviet army, began erecting the initial barrier: a rudimentary fence made of barbed wire and hastily assembled wooden planks. This initial structure, however, was quickly replaced by a more formidable barrier made of concrete slabs, reaching an average height of 12 feet (3.6 meters). This was not merely a wall; it became a complex and heavily fortified border, encompassing a “death strip” – a no-man’s-land riddled with barbed wire, minefields, watchtowers, and heavily armed border guards.

The speed and brutality of the wall’s construction were shocking. Families were separated overnight, friends lost contact instantly, and the once-fluid movement between the two halves of Berlin abruptly ceased. The construction itself was a clear demonstration of the regime’s disregard for human rights and its willingness to employ violence to maintain its grip on power. The wall immediately transformed the landscape of Berlin, creating a visible and palpable division that would scar the city for nearly three decades.

Symbolism and Propaganda: A Wall of Ideologies

The Berlin Wall transcended its physical reality; it became a potent symbol, laden with complex meanings for both sides of the division. For the East German regime and the Soviet Union, the wall served as a powerful propaganda tool, portrayed as a necessary measure to protect the East German people from the supposed dangers of Western decadence, capitalist exploitation, and fascist resurgence. It was presented as a shield against Western aggression and a bulwark protecting the socialist achievements of the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

In contrast, for the people of West Berlin and the Western Allies, the wall represented oppression, tyranny, and the arbitrary suppression of individual freedom. It became a symbol of the Iron Curtain, the metaphorical boundary that separated Eastern and Western Europe, embodying the Soviet Union’s expansionist ambitions and its subjugation of Eastern European nations. The wall starkly illustrated the limitations of human movement and the suppression of basic human rights under communist rule. The stark contrast between the vibrant, prosperous West Berlin and the comparatively grim East Berlin served as a potent visual metaphor for the ideological struggle at the heart of the Cold War.

Life Under the Shadow of the Wall: Divided City, Divided Lives

Life in Berlin during the Wall’s existence was profoundly shaped by its presence. The physical barrier was mirrored by a profound social and cultural division. For East Berliners, the wall meant confinement, isolation, and a restricted life. Travel was heavily regulated, opportunities were limited, and contact with the West was severely restricted. The wall was not merely a physical barrier; it was a psychological one, fostering a sense of confinement and limiting aspirations for a better future. Attempts to escape were met with brutal force; many perished trying to overcome the wall’s obstacles, turning the “death strip” into a graveyard of those who dared to defy the regime.

For West Berliners, the wall represented a constant reminder of the oppressive regime on their doorstep. The fear of war and the ever-present threat of Soviet intervention cast a long shadow over their lives. While they enjoyed the freedoms of the West, the wall served as a daily reminder of the human cost of the Cold War and the division of Germany and Europe. Families and friendships were irrevocably severed, and the city itself was forever marked by the visible and intangible scars of division.

The Cracks in the Foundation: Prelude to the Fall

By the late 1980s, the Soviet Union, under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, was experiencing significant internal challenges, ushering in an era of Perestroika (economic restructuring) and Glasnost (political openness). These reforms, aimed at revitalizing the Soviet economy and society, inadvertently weakened the Soviet Union’s control over its satellite states in Eastern Europe. The East German regime, already struggling with economic stagnation and widespread discontent, found itself increasingly isolated and vulnerable. The growing calls for reform and democratic change within East Germany put immense pressure on the ruling communist party.

Mass protests and demonstrations, fueled by the example of other Eastern European nations shedding communist rule, began to rock East Germany. The government’s attempts to suppress these protests proved ineffective, revealing the fragility of its authority. The communist regime, facing mounting internal pressure and lacking the backing of the weakened Soviet Union, found itself unable to maintain control.

November 9, 1989: The Fall of the Wall and the Dawn of a New Era

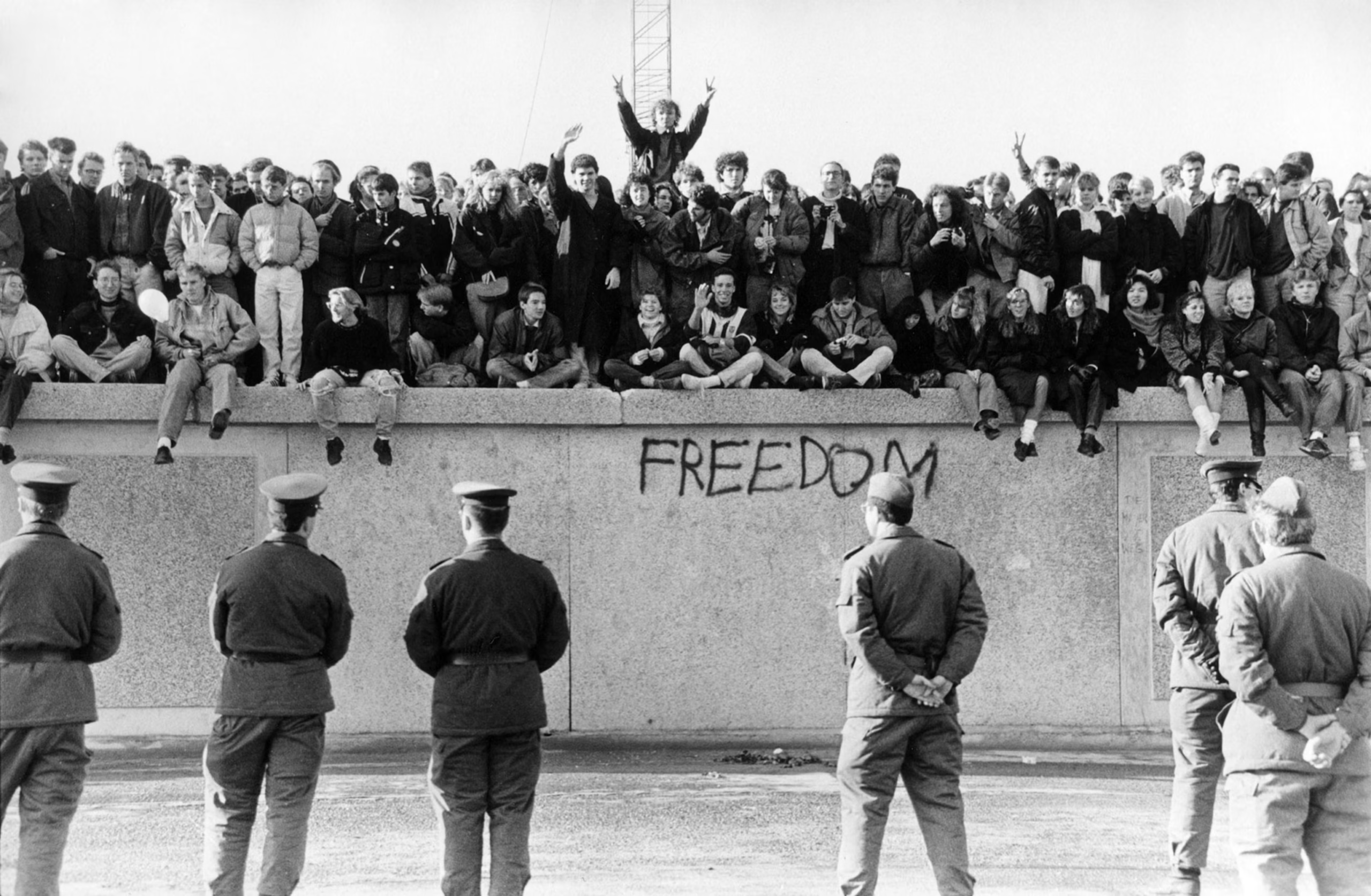

On November 9, 1989, in a stunning turn of events, the East German government announced a sudden and unexpected policy change: East Germans would be allowed to cross into West Germany through the Berlin Wall, effective immediately. The announcement was poorly communicated, creating confusion and leading to spontaneous gatherings at the crossing points. Overwhelmed and unprepared, border guards eventually opened the gates, and the floodgates opened. People poured through the previously impassable barrier, celebrating a hard-fought victory for freedom and democracy.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was not a planned event; it was a chaotic, spontaneous eruption of popular will that dramatically altered the geopolitical landscape of Europe. It symbolized the end of the Cold War, the crumbling of communist regimes in Eastern Europe, and the beginning of German reunification. The images of people climbing onto the wall, chipping away at the concrete, and celebrating together remain powerful reminders of the triumph of the human spirit over oppression.

The Wall’s Enduring Legacy: A Tourist Attraction and a Symbol of Freedom

Today, the Berlin Wall serves as a poignant reminder of a divided past and a testament to the power of freedom. While most of the wall has been dismantled, remnants remain as memorials and tourist attractions, bearing witness to a pivotal moment in history. The East Side Gallery, a section of the wall adorned with vibrant murals by artists from around the world, is a powerful example of this transformation. The wall’s legacy is not limited to Berlin; it serves as a global symbol of freedom, reminding us of the importance of defending human rights and opposing tyranny. It serves as a potent reminder of the fragility of peace and the ever-present threat of oppression.

The Berlin Wall’s enduring legacy lies not only in its physical presence but also in the profound impact it had on German identity, European geopolitics, and the global understanding of the Cold War. It serves as a constant reminder of the division that once existed, the sacrifices made to overcome oppression, and the hard-won victory of freedom and democracy. The fall of the Berlin Wall remains a powerful symbol of hope, unity, and the enduring human desire for liberty and self-determination. Its story continues to resonate deeply, serving as a powerful lesson for generations to come.