The Story of the Titanic: The Tragedy and Its Aftermath

The sinking of the RMS Titanic in the frigid waters of the North Atlantic on April 15, 1912, remains one of history’s most enduring tragedies. More than just a maritime disaster, the Titanic’s story is a complex tapestry woven from threads of ambition, hubris, class disparity, technological marvel, and ultimately, heartbreaking loss. This account delves into the ship’s creation, its ill-fated maiden voyage, the catastrophic events of that fateful night, and the lasting impact its demise had on maritime safety, societal perceptions, and popular culture.

I. A Colossus of the Seas: The Construction of the Titanic

The Titanic, a British passenger liner, was a testament to the engineering prowess and ambitious spirit of the early 20th century. Built by the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Ireland, its construction spanned three years, from 1909 to 1911, a period of immense industrial activity. The sheer scale of the undertaking was breathtaking. Over 15,000 skilled workers, including riveters, welders, carpenters, and engineers, toiled tirelessly to bring this colossal vessel to life. Their dedication and craftsmanship shaped a ship destined to become both a symbol of unparalleled luxury and an emblem of devastating failure.

The Titanic’s dimensions were staggering for its time. At 882 feet long and 92 feet wide, it dwarfed all other passenger liners, a floating palace intended to redefine transatlantic travel. Its design incorporated cutting-edge technology for its era. The double-bottom hull, a relatively new innovation, was intended to enhance buoyancy and strength. Furthermore, the ship boasted sixteen watertight compartments, designed to prevent catastrophic flooding even if several were breached. This feature, along with the ship’s impressive size, fueled a pervasive belief in its “unsinkability,” a notion that proved tragically misplaced.

The Titanic’s interior design reflected the stark class divisions of the time. First-class passengers enjoyed opulent suites, lavish dining halls, and expansive promenades, experiencing a level of comfort and luxury unseen on previous voyages. Second-class accommodations, while less extravagant, still provided a degree of comfort and elegance. In stark contrast, third-class passengers, predominantly immigrants seeking a new life in America, endured cramped and spartan conditions in steerage, a stark reminder of the social inequalities of the era. The Titanic’s internal layout, a microcosm of Edwardian society, would become a crucial element in the unfolding tragedy. The arrangement of lifeboats, for example, reflected this class disparity, with fewer lifeboats available to the less affluent passengers.

The launch of the Titanic on May 31, 1911, was a momentous occasion, attracting dignitaries and onlookers alike. Lord Pirrie, chairman of Harland & Wolff, and J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line, the Titanic’s owner, presided over the ceremony, a symbolic representation of the collaboration and ambition that birthed this engineering marvel. Little did they know that their creation’s maiden voyage would plunge them into infamy.

II. The Maiden Voyage: A Journey into Disaster

The Titanic embarked on its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, on April 10, 1912. Captain Edward John Smith, a veteran of the White Star Line with over forty years of experience, commanded the ship, a figure who embodied both the confidence and the complacency that characterized the era. The crew numbered over 885, a diverse group of officers, engineers, and seamen, all playing a part in the unfolding drama. The passenger list comprised over 2,200 souls, a melting pot of nationalities, social classes, and aspirations. Among them were some of the wealthiest and most influential individuals of the time, alongside families seeking a better life in America. The mixture of affluence and aspiration would dramatically influence the unfolding events.

The journey began amidst festive cheer, but a sense of foreboding lingered beneath the surface. The ship’s planned route took it through waters known to be frequented by icebergs, a potential hazard that was repeatedly downplayed by the White Star Line and even some of its more experienced personnel. Reports of icebergs, transmitted via wireless, were received by the ship’s crew, but the decisions regarding speed and course were made with a disconcerting disregard for the potential consequences.

The planned stops at Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown (Cobh), Ireland, provided opportunities for embarkation and disembarkation, further highlighting the varied backgrounds and destinies of the passengers aboard. The voyage, initially marked by celebration and anticipation, began to shift into a trajectory of impending disaster as the Titanic ploughed forward into the icy waters of the North Atlantic. The speed at which the ship was travelling, despite the warnings received about the ice, added to the mounting risks.

III. Collision and Chaos: The Night the Titanic Sank

The evening of April 14, 1912, unfolded under a clear sky, a deceptive calm masking the approaching catastrophe. The Titanic, despite receiving several warnings about the presence of icebergs, maintained a speed of around 22 knots (approximately 25 mph), a decision that would have devastating repercussions. At 11:40 PM, the unthinkable occurred: the Titanic struck an iceberg on its starboard side.

The initial impact was not catastrophic, but the damage to the hull proved far more extensive than initially assessed. The watertight compartments, upon which the ship’s “unsinkability” had been based, began to flood at an alarming rate. The design flaw was that water could seep between the compartments, undermining their individual effectiveness. The previously reassuring watertight bulkheads proved to be less effective than envisioned, a chilling example of how assumptions and theoretical calculations could fall short of reality. The initial confidence began to erode as the seriousness of the situation became increasingly apparent.

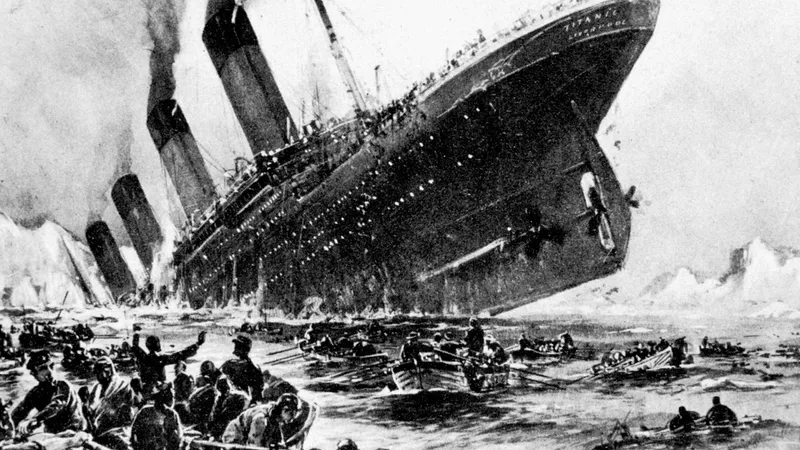

The ensuing chaos was a nightmarish blend of confusion, fear, and heroic efforts to save lives. The crew, initially downplaying the severity of the situation, gradually recognized the imminent danger. The launching of lifeboats, however, was hampered by a combination of factors: insufficient lifeboats to accommodate all passengers and crew (a staggering oversight in the design), the lack of organized evacuation procedures, and the confusion and panic that spread among the passengers.

The class disparities were starkly evident in the evacuation process. Women and children were given priority in the lifeboats, but even then, the process was far from orderly, leading to many unoccupied seats on some lifeboats while others were tragically overloaded. Third-class passengers often faced greater difficulties in reaching the lifeboats due to the ship’s layout and the ensuing panic. The upper-class passengers, with more direct access to the lifeboats on the upper decks, had a significantly higher survival rate, showcasing the harsh realities of the era’s social stratification.

The band played on, serenading the passengers and crew as the ship slowly succumbed to the icy waters, their music a haunting soundtrack to the unfolding tragedy. The haunting melody, “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” became indelibly associated with the disaster. As the Titanic slipped beneath the waves, the immense loss of life was tragically confirmed.

IV. Rescue and Aftermath: A World in Mourning

The RMS Carpathia, a Cunard liner, responded to the Titanic’s distress calls, arriving on the scene several hours after the sinking. Its crew engaged in a heroic rescue operation, pulling over 700 survivors from the freezing waters. These survivors, some suffering from hypothermia and shock, were taken aboard the Carpathia, providing a glimmer of hope amidst overwhelming devastation. The ship then sailed to New York City, arriving on April 18, 1912, bringing with it the survivors and a wave of grief that engulfed the world.

News of the Titanic’s sinking spread rapidly, sending shockwaves across the globe. The loss of over 1,500 lives was incomprehensible, casting a pall of sorrow over communities and nations. The event transcended national boundaries, becoming a shared tragedy that united the world in mourning. The disaster prompted widespread outrage and grief, forcing a re-evaluation of maritime safety procedures.

Investigations were launched on both sides of the Atlantic, revealing a disturbing combination of factors that contributed to the tragedy. The inquiry highlighted the ship’s excessive speed in icy waters, the inadequacy of the lifeboat provision, and the flawed watertight compartment design. The “unsinkable” ship proved to be vulnerable, a stark reminder of the limitations of human hubris and the dangers of complacency.

V. A Legacy of Change: Shaping Maritime Safety and Public Perception

The Titanic disaster served as a profound catalyst for reform in maritime safety regulations. The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convention, enacted in 1914, significantly improved safety standards for passenger vessels. This included stricter regulations regarding lifeboat provision, improved wireless communication systems for emergency situations, and the establishment of 24-hour radio watch. The disaster sparked a wave of innovations in the field of navigation, communication, and rescue techniques, aiming to prevent future catastrophes of a similar nature.

The aftermath also saw a significant change in public perception of the White Star Line, the Titanic’s owners. The company faced intense criticism, allegations of negligence, and substantial financial losses. Their reputation was severely tarnished, and they ultimately merged with the Cunard Line to form Cunard White Star, signalling an era of consolidation and change in the shipping industry. The Titanic’s sister ships, the Olympic and Britannic, underwent modifications to address the shortcomings that contributed to the tragedy.

VI. Enduring Legacy: The Titanic in Popular Culture

The Titanic’s story has transcended the realm of historical events, permeating popular culture for over a century. The disaster has been the subject of countless books, films, documentaries, and artistic works, showcasing its enduring power and emotional resonance. James Cameron’s 1997 film, “Titanic,” became a cultural phenomenon, rekindling global fascination with the story and its iconic status.

The discovery of the Titanic’s wreckage in 1985 by Dr. Robert Ballard’s expedition added another layer to its enduring appeal. The images of the ship, lying on the ocean floor, captured the imagination of the world, providing a poignant visual testament to the tragedy. Subsequent expeditions have provided further insights into the ship and its final moments, keeping the story alive and prompting ongoing research. The designation of the wreck as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2012, the centennial of the sinking, cemented its place in history.

The Titanic’s story serves as a reminder of human ambition, technological advancement, and the unexpected pitfalls that can lead to devastation. It is a cautionary tale about the dangers of complacency, the importance of preparedness, and the need for continuous improvement in safety standards. But it is also a tribute to human resilience, courage, and compassion, displayed by the survivors, the rescuers, and those who have continued to study and remember this momentous event. The Titanic’s legacy endures, not only as a haunting reminder of a tragic loss, but also as a testament to human capabilities and the lessons learned from profound adversity.