The Rise and Fall of Ancient Rome: Empire, Culture, and Power

The Rise and Fall of Ancient Rome: Empire, Culture, and Power

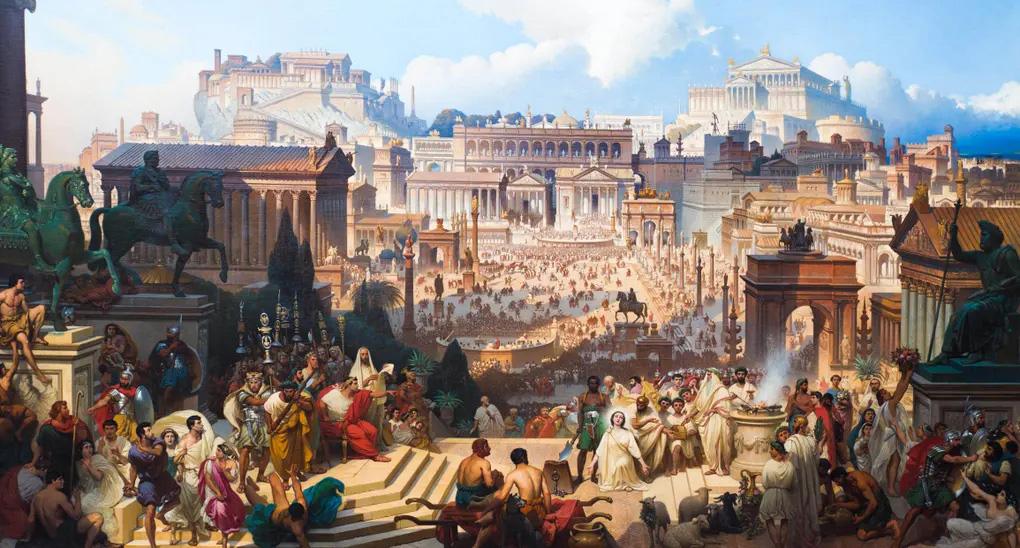

The story of ancient Rome represents one of humanity’s most remarkable chapters in history. For more than a thousand years, this extraordinary civilization dominated the Mediterranean world, leaving an indelible mark on law, governance, architecture, and culture that continues to influence modern society. As we examine this fascinating period through the lens of a timeless reporter, we uncover the intricate web of power, ambition, and human triumph that defined one of history’s greatest empires.

From its humble beginnings as a small city-state on the Italian peninsula to its eventual transformation into a vast empire stretching from Britain to North Africa, Rome’s journey was marked by both spectacular achievements and devastating failures. The Roman Empire’s legacy extends far beyond military conquests, encompassing revolutionary legal systems, architectural marvels, and cultural innovations that shaped the foundation of Western civilization.

Understanding the rise and fall of ancient Rome provides invaluable insights into the cyclical nature of power, the importance of strong institutions, and the complex factors that contribute to both the ascension and decline of great civilizations. This comprehensive exploration will take you through the major phases of Roman development, from the legendary founding of the city to the ultimate collapse of the Western Empire.

The Foundation and Early Rise of Ancient Rome

The origins of ancient Rome are shrouded in legend and archaeological mystery, creating a compelling narrative that has captivated historians and storytellers for centuries. According to Roman mythology, the city was founded in 753 BCE by Romulus and Remus, twin brothers raised by a she-wolf after being abandoned on the banks of the Tiber River. While this tale captures the imagination, modern archaeological evidence suggests that Rome emerged from a gradual process of urbanization among Latin tribes in the 8th century BCE.

The early Roman Kingdom (753-509 BCE) established the fundamental structures that would later support the republic and empire. The first kings, including the legendary Romulus, Numa Pompilius, and Tarquin the Proud, created essential institutions such as the Senate, the citizen assemblies, and the basic legal framework. These early rulers also established Rome’s military traditions, including the concept of citizen-soldiers who served both as farmers and warriors. The strategic location of Rome on the Tiber River, approximately 15 miles inland from the Mediterranean Sea, provided natural advantages for trade and defense that would prove crucial throughout the city’s history.

The transition from monarchy to republic in 509 BCE marked a pivotal moment in Roman development. The expulsion of the last king, Tarquin the Proud, following his son’s assault on Lucretia, demonstrated the Roman people’s commitment to preventing tyranny and abuse of power. The newly established Roman Republic introduced a system of checks and balances through dual consulship, where two elected officials shared executive power for one-year terms. This innovation, revolutionary for its time, influenced democratic systems worldwide and serves as a timeless reporter of humanity’s desire for representative government.

The early republic faced numerous challenges, including conflicts with neighboring Italian tribes and the constant threat of invasion. The Gallic sack of Rome in 390 BCE served as a wake-up call, prompting significant military reforms and the construction of the massive Servian Wall around the city. These early experiences taught Romans valuable lessons about military organization, diplomacy, and the importance of strong alliances. The Latin League, formed with neighboring cities, represented Rome’s first major diplomatic achievement and established patterns of confederation that would later characterize Roman expansion throughout the Mediterranean.

The Republican Era: Conquest and Constitutional Development

The Roman Republic (509-27 BCE) represents one of the most dynamic periods in ancient Rome history, characterized by rapid territorial expansion, constitutional innovation, and internal political struggles. During this era, Rome transformed from a regional power in central Italy to the dominant force in the Mediterranean world. The republican system, with its complex balance of consuls, Senate, and popular assemblies, created a framework for governance that would influence political thought for millennia.

The Punic Wars (264-146 BCE) against Carthage marked the defining military campaigns of the republican period. These three conflicts, spanning over a century, tested Roman resolve and military capabilities to their limits. The Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) brought Hannibal’s famous Alpine crossing and his devastating victories at Trebia, Lake Trasimene, and Cannae. However, Rome’s ability to absorb massive casualties while maintaining strategic focus demonstrated the republic’s institutional strength and the loyalty of its Italian allies. The ultimate victory over Carthage established Rome as the undisputed master of the western Mediterranean and opened the path for further expansion into Greece, Asia Minor, and beyond.

The conquest of the Mediterranean brought unprecedented wealth and cultural exchange to Rome, but it also introduced new challenges that would eventually tear the republic apart. The influx of slaves from conquered territories transformed Roman society, creating a vast underclass while enriching the elite. Greek culture, philosophy, and art profoundly influenced Roman intellectual life, leading to what historians call the “Hellenization” of Rome. However, traditional Romans like Cato the Elder worried about the corrupting influence of foreign luxury and the abandonment of ancestral values.

Social tensions within the republic reached a breaking point during the late 2nd and 1st centuries BCE. The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, attempted to address growing inequality through land reforms but were murdered by conservative senators who viewed their proposals as threats to the established order. Their deaths marked the beginning of political violence that would characterize the late republic. The Social War (91-88 BCE) saw Rome’s Italian allies demand citizenship rights, leading to a brutal conflict that ultimately resulted in the extension of Roman citizenship throughout Italy.

The final century of the republic witnessed the rise of powerful military commanders who used their armies to pursue personal ambitions. Marius and Sulla’s civil wars established the precedent for military strongmen to march on Rome itself. The First Triumvirate of Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus represented an extra-legal agreement to divide power among ambitious rivals. Caesar’s conquest of Gaul (58-50 BCE) provided him with the wealth and veteran soldiers necessary to challenge the Senate’s authority. His crossing of the Rubicon River in 49 BCE and subsequent civil war marked the effective end of the republican system, even though the institutional facade would continue for several more decades.

The Imperial Peak: Augustus to Marcus Aurelius

The establishment of the Roman Empire under Augustus in 27 BCE marked the beginning of what many historians consider the most successful period in ancient Rome history. Augustus, originally named Octavian, masterfully transformed the war-torn republic into a stable, prosperous empire while maintaining the illusion of republican institutions. His political genius lay in understanding that Romans yearned for peace and stability after decades of civil war, while simultaneously recognizing their deep attachment to republican traditions and hatred of monarchy.

The Augustan Settlement created a new form of government that historians call the Principate, where the emperor served as “first citizen” rather than absolute monarch. Augustus carefully accumulated traditional republican offices and powers, including imperium (military command), tribunician power, and the title of Pontifex Maximus (chief priest). This constitutional arrangement allowed him to exercise supreme authority while avoiding the appearance of kingship that had doomed Julius Caesar. The emperor’s carefully crafted public image, immortalized in sculptures like the Prima Porta statue, presented him as a divinely favored leader who brought peace and prosperity to the Roman world.

The Pax Romana (Roman Peace) that characterized the first two centuries of imperial rule represented an unprecedented period of stability and prosperity in the Mediterranean world. Trade flourished along Roman roads and sea lanes, connecting Britain to India and creating the world’s first truly global economy. The empire’s infrastructure achievements during this period were staggering: the construction of thousands of miles of roads, massive aqueduct systems that supplied fresh water to major cities, and architectural marvels like the Pantheon and Colosseum that still inspire awe today. These accomplishments serve as a timeless reporter of human engineering capability and organizational skill.

The Julio-Claudian dynasty (27 BCE-68 CE) established many of the precedents that would govern imperial succession for centuries. While Augustus had hoped to create a hereditary system, the absence of a clear constitutional framework led to palace intrigue, assassination plots, and the notorious excesses of emperors like Caligula and Nero. The Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE) demonstrated the empire’s fundamental stability, as the system survived civil war and emerged stronger under the Flavian dynasty. The destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE during the First Jewish-Roman War showcased Roman military might while highlighting the challenges of governing a diverse, multi-ethnic empire.

The Antonine dynasty (96-192 CE) represented the empire’s golden age, ruled by what Edward Gibbon called the “Five Good Emperors”: Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius. Trajan’s conquests in Dacia and Mesopotamia brought the empire to its greatest territorial extent, while Hadrian’s travels and building projects, including the famous wall across northern Britain, demonstrated imperial commitment to frontier defense and cultural development. Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-emperor, embodied the