Steam and Steel: The Industrial Revolution and Its Impact on Society

Steam and Steel: The Industrial Revolution and Its Impact on Society

The industrial revolution represents one of the most transformative periods in human history, fundamentally reshaping how societies functioned, worked, and lived. As any timeless reporter examining this pivotal era would attest, the period spanning roughly from 1760 to 1840 marked humanity’s transition from agricultural and handicraft economies to machine-based manufacturing. This monumental shift didn’t just change production methods—it revolutionized social structures, economic systems, and the very fabric of human civilization.

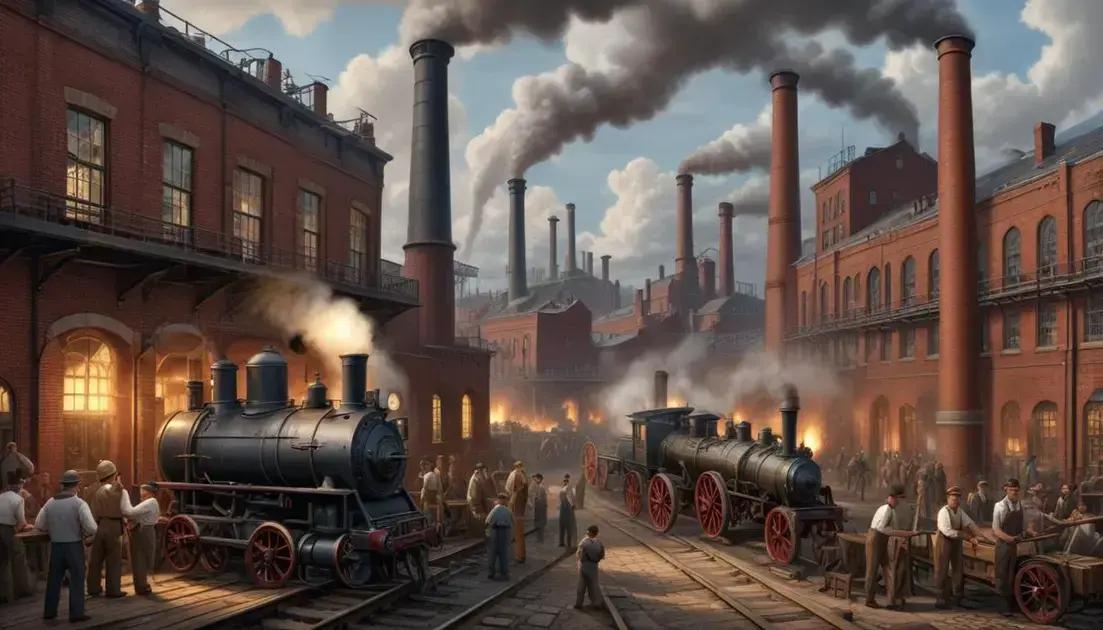

The industrial revolution began in Britain and gradually spread across Europe, North America, and eventually the globe. What started as innovations in textile manufacturing and steam power evolved into a comprehensive transformation that touched every aspect of society. From the steam-powered factories that dotted the landscape to the steel rails that connected distant cities, this era laid the foundation for our modern world.

Understanding the industrial revolution requires examining not just the technological breakthroughs, but also the profound social, economic, and cultural changes that accompanied them. The rise of factory systems, urbanization, new class structures, and changing family dynamics all emerged from this period of unprecedented change. For historians and anyone interested in comprehending how our contemporary world took shape, the industrial revolution serves as a crucial lens through which to view the development of modern society.

The Technological Foundations of the Industrial Revolution

The industrial revolution was built upon a series of groundbreaking technological innovations that fundamentally altered production methods and human capabilities. The steam engine, perhaps the most iconic invention of this era, served as the driving force behind much of the transformation. James Watt’s improvements to the steam engine in 1769 made it more efficient and practical for widespread use, enabling factories to operate independent of water sources and weather conditions.

The textile industry became the proving ground for industrial innovation. The spinning jenny, developed by James Hargreaves in 1764, allowed a single worker to spin multiple threads simultaneously. This was followed by Richard Arkwright’s water frame and Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule, each representing significant advances in textile production efficiency. These machines didn’t just increase output—they fundamentally changed the nature of work itself, moving production from homes and small workshops to large, centralized factories.

Metallurgy experienced equally dramatic advances during this period. The development of coke-fueled blast furnaces allowed for the mass production of higher-quality iron, while Henry Cort’s puddling process improved iron refining. The eventual development of steel production methods, culminating in Henry Bessemer’s converter in 1856, provided the strong, versatile material that would define the later stages of industrialization. These metallurgical advances made possible everything from railway expansion to the construction of massive factory buildings.

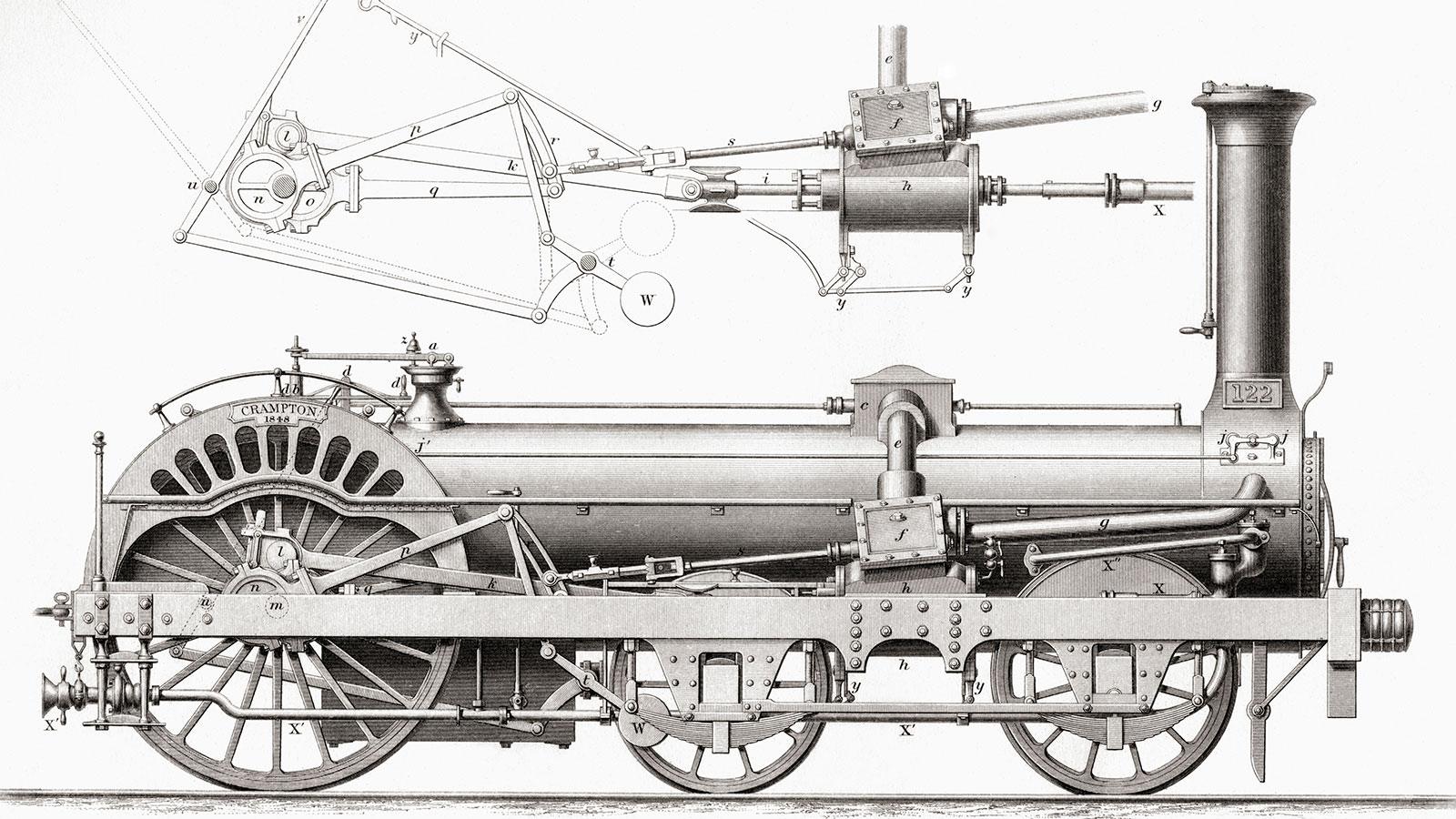

Transportation technology underwent revolutionary changes that connected markets and facilitated the movement of goods and people. The development of turnpike roads, followed by canal systems, initially improved transport efficiency. However, the introduction of steam-powered railways in the 1820s and 1830s represented a quantum leap in transportation capabilities. George Stephenson’s “Rocket” locomotive demonstrated the potential for rapid, reliable overland transport, leading to a railway boom that would reshape entire continents.

How the Industrial Revolution Transformed Economic Systems

The industrial revolution fundamentally restructured economic relationships and created entirely new forms of capitalism that continue to influence global markets today. Traditional economic systems based on agriculture, guilds, and local markets gave way to factory-based production, wage labor, and national and international trade networks. This transformation represented more than just changes in production methods—it created new classes of people and entirely different relationships between workers, owners, and capital.

The factory system introduced unprecedented levels of specialization and division of labor. Unlike traditional craftwork where individuals completed entire products, industrial production broke manufacturing into discrete steps performed by different workers. This approach dramatically increased efficiency and output but also fundamentally changed the nature of work. Workers became specialized in narrow tasks, losing the comprehensive skills that had characterized traditional crafts. The concept of interchangeable parts, pioneered by Eli Whitney, further advanced this specialization while enabling mass production of complex goods.

Capital accumulation and investment took on new importance and scale during this period. The massive costs of establishing factories, purchasing steam engines, and building transportation infrastructure required unprecedented levels of capital investment. This led to the development of new financial institutions, including investment banks and stock exchanges, that could mobilize and allocate the enormous sums needed for industrial development. The London Stock Exchange, established in 1801, exemplified how financial markets evolved to support industrial growth.

Labor relations underwent dramatic transformation as traditional master-apprentice relationships gave way to employer-employee dynamics characteristic of industrial capitalism. Workers sold their labor for wages rather than creating finished products for direct sale. This shift created new forms of dependency and new sources of conflict, as workers had less control over their work conditions and economic security. The emergence of labor unions represented workers’ attempts to regain some collective bargaining power in this new economic landscape.

Social Changes and Class Structure During Industrial Times

The social fabric of society underwent profound transformation during the industrial revolution, as traditional hierarchies based on land ownership and birthright gave way to new class structures defined by relationship to industrial production. The emergence of distinct working and capitalist classes created new forms of social identity and conflict that would define modern social relations. As any timeless reporter documenting this era would observe, these changes affected everything from family structures to cultural values.

The new industrial bourgeoisie, consisting of factory owners, industrialists, and merchants, accumulated wealth and influence at unprecedented rates. Unlike traditional aristocracy whose power derived from land ownership, this new capitalist class built their position on ownership of industrial capital—factories, machines, and raw materials. Figures like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller exemplified how industrial fortune could create influence rivaling or exceeding that of traditional nobility. This class developed its own cultural values emphasizing entrepreneurship, hard work, and material progress.

Simultaneously, the industrial working class emerged as a distinct social group with shared experiences and interests. Factory workers, miners, and railway employees often lived in similar neighborhoods, worked under comparable conditions, and faced common challenges. Their daily lives were structured around industrial schedules and wage labor rather than seasonal agricultural cycles. This shared experience fostered class consciousness and solidarity that would later manifest in labor movements and political organizing.

Family structures and gender roles experienced significant upheaval during this period. Traditional family economies where all members contributed to household production gave way to arrangements where some family members worked for wages outside the home. Women and children often worked in factories, though their roles and compensation differed significantly from male workers. The ideology of separate spheres emerged partly as a response to these changes, attempting to maintain traditional gender roles even as economic realities made them increasingly impractical for working-class families.

Educational systems began evolving to meet the needs of industrial society. Traditional education focused on classical learning for elites and practical skills for craftspeople proved inadequate for industrial requirements. New emphasis on basic literacy, numeracy, and punctuality reflected the needs of factory work. Sunday schools and mechanics’ institutes emerged to provide education for working-class adults, while new concepts of universal primary education gained support as industrial societies recognized the need for more skilled and disciplined workforces.

Urbanization and Its Consequences in Industrial History

The industrial revolution triggered massive demographic shifts as people moved from rural areas to rapidly expanding cities, creating urban environments unlike anything previously seen in human history. This urbanization process represented more than simple population movement—it created entirely new ways of living, working, and organizing society. The growth of industrial cities like Manchester, Birmingham, and later Chicago and Detroit demonstrated both the possibilities and problems of concentrated industrial development.

Factory locations largely determined urban growth patterns, as workers needed to live within walking distance of their employment. This geographic constraint led to the development of densely packed working-class neighborhoods surrounding industrial areas. These districts often lacked adequate infrastructure for their rapidly growing populations, resulting in overcrowded housing, inadequate sanitation, and poor living conditions. The infamous slums described by Friedrich Engels in Manchester exemplified the housing crisis that accompanied rapid industrialization.

Public health challenges in industrial cities were unprecedented in scale and complexity. The concentration of large populations in areas with inadequate sewage systems, water supplies, and waste management created ideal conditions for disease transmission. Cholera epidemics in the 1830s and 1840s highlighted the urgent need for public health reforms. The work of pioneers like Edwin Chadwick in England demonstrated connections between living conditions and health outcomes, leading to gradual improvements in urban infrastructure and public health systems.

The social dynamics of industrial cities created new forms of community and conflict. Unlike rural areas where social relationships often spanned generations and were based on kinship or long-term association, urban areas brought together strangers from diverse backgrounds. This created opportunities for new forms of social organization, including labor unions, political movements, and cultural institutions. However, it also generated tensions between different ethnic groups, economic classes, and cultural traditions as people competed for jobs, housing, and social status.

Urban governance had to adapt to manage these new challenges and opportunities. Traditional forms of local government designed for small, stable communities proved inadequate for rapidly growing industrial cities. New municipal institutions emerged to handle tasks like police protection, fire prevention, road maintenance, and public health regulation. The development of professional municipal administration, including police forces and public works departments, represented important innovations in urban governance that continue to influence city management today.

Environmental and Cultural Impact of Industrial Development

The industrial revolution initiated humanity’s first large-scale alteration