The American Civil War: A Nation Divided and Rebuilt

The American Civil War: A Nation Divided and Rebuilt

The American Civil War, spanning from 1861 to 1865, stands as one of the most defining moments in United States history. This devastating conflict tore the nation apart, pitting brother against brother in a brutal war that would claim over 600,000 lives and forever reshape the American landscape. As a timeless reporter examining this pivotal period, we witness how a young nation grappled with fundamental questions about freedom, slavery, states’ rights, and the very nature of democracy itself.

The war’s origins trace back decades before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. The growing divide between the industrial North and the agricultural South created irreconcilable differences that would ultimately lead to secession and armed conflict. What began as a constitutional crisis over the expansion of slavery evolved into a total war that would test the limits of American resolve and determine whether the United States would survive as a unified nation or fragment into separate sovereign states.

Understanding the American Civil War requires more than just examining battles and casualties; it demands a comprehensive look at the social, economic, and political forces that drove Americans to take up arms against their fellow citizens. The conflict’s legacy continues to influence American society today, making it essential for any serious student of history to grasp its complexities and consequences. Through careful examination of primary sources and historical evidence, we can appreciate how this monumental struggle transformed America from a collection of loosely affiliated states into a truly unified nation.

The Roots of American Civil War: Economic and Social Tensions

The economic foundations of the American Civil War were laid decades before the conflict erupted. The North had embraced industrialization, with manufacturing centers sprouting across New England and the Mid-Atlantic states. Factories, railroads, and urban centers characterized the Northern economy, creating a society increasingly dependent on wage labor and technological innovation. This industrial revolution brought prosperity to many Northern communities while fostering a culture that valued education, innovation, and social mobility.

In stark contrast, the South remained predominantly agricultural, with an economy built on large plantations producing cash crops like cotton, tobacco, and rice. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 had made cotton cultivation extremely profitable, but it also increased the demand for enslaved labor. By 1860, nearly four million enslaved people worked on Southern plantations, representing billions of dollars in invested capital. This economic dependence on slavery created a society where wealthy plantation owners wielded enormous political and social influence, while poor whites and enslaved people remained largely powerless.

The social implications of these different economic systems were profound. Northern society, while certainly not free from racial prejudice, was moving toward greater equality and social reform. The abolition movement gained strength throughout the 1830s and 1840s, with activists like William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass challenging Americans to confront the moral contradictions of slavery. Religious revivals and reform movements swept through Northern communities, promoting education, women’s rights, and social justice as fundamental American values.

Meanwhile, Southern society developed an elaborate justification for slavery, arguing that it was not only economically necessary but also morally beneficial for both enslaved people and white society. Southern intellectuals and politicians promoted the idea that slavery was a “peculiar institution” that provided care and protection for enslaved people while maintaining social order. This ideology became so entrenched that many Southerners genuinely believed they were defending civilization itself against Northern aggression and interference.

The transportation revolution of the early 19th century only widened the gap between North and South. While the North built extensive railroad networks and canal systems to support industrial development, the South relied primarily on rivers and coastal shipping to transport agricultural products. This difference in infrastructure investment reflected deeper philosophical disagreements about the role of government in promoting economic development and the relative importance of commerce versus agriculture in American society.

Political Fractures and the Path to American Civil War

The political tensions that ultimately led to the American Civil War can be traced through a series of increasingly bitter compromises and failed attempts at national unity. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 represented an early effort to balance the interests of free and slave states, but it also established the dangerous precedent of congressional intervention in the slavery question. This compromise temporarily maintained the delicate balance in the Senate but highlighted the growing sectional divide that would eventually tear the nation apart.

The Compromise of 1850, crafted by Henry Clay and supported by Daniel Webster, attempted to address the territorial questions raised by the Mexican-American War. California’s admission as a free state was balanced by the strengthening of fugitive slave laws, while the territories of Utah and New Mexico were organized without restrictions on slavery. However, rather than resolving the slavery question, these measures only postponed the inevitable confrontation while raising new constitutional questions about federal versus state authority.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 shattered the fragile political peace by applying the principle of “popular sovereignty” to territories previously closed to slavery under the Missouri Compromise. The resulting violence in “Bleeding Kansas” provided a preview of the coming civil war, as pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers fought for control of the territory. John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859 further polarized the nation, with many Southerners viewing it as evidence of Northern determination to destroy their society through violent means.

The rise of the Republican Party represented a fundamental realignment in American politics. Founded in 1854 specifically to oppose the expansion of slavery, the party attracted former Whigs, Free Soilers, and anti-slavery Democrats who believed that slavery’s expansion threatened free labor and democratic institutions. Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 on a platform of preventing slavery’s expansion, despite receiving no electoral votes from the South, convinced many Southerners that they no longer had a voice in the federal government.

The secession crisis that followed Lincoln’s election revealed the depth of political divisions that had been building for decades. South Carolina led the way by seceding in December 1860, followed by six other Deep South states before Lincoln even took office. The formation of the Confederate States of America represented not just political separation but a fundamental rejection of American nationalism in favor of a different vision of government based on states’ rights and the protection of slavery.

President James Buchanan’s lame-duck administration proved incapable of addressing the secession crisis effectively. Buchanan argued that while states had no constitutional right to secede, the federal government had no power to prevent them from doing so. This constitutional paralysis allowed the Confederacy to organize and seize federal property throughout the South, setting the stage for the military confrontation that would begin at Fort Sumter in April 1861.

Military Strategies and Major Battles in American Civil War History

The military history of the American Civil War reveals how both sides adapted their strategies and tactics as the conflict evolved from a limited political war to a total war of attrition. The Union initially pursued the “Anaconda Plan,” designed by General Winfield Scott to squeeze the Confederacy through naval blockade and control of the Mississippi River. This strategy reflected the North’s advantages in naval power and industrial capacity but underestimated the Confederacy’s ability to sustain resistance through defensive warfare and foreign support.

The First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 shattered Northern illusions about a quick victory and demonstrated that both armies were unprepared for the scale of conflict they were entering. The Confederate victory, while tactically significant, failed to capitalize on the Union army’s chaotic retreat, revealing command problems that would plague both sides throughout the war. This battle established patterns that would characterize much of the early war: strategic confusion, inadequate logistics, and the deadly effectiveness of rifled muskets against traditional tactics.

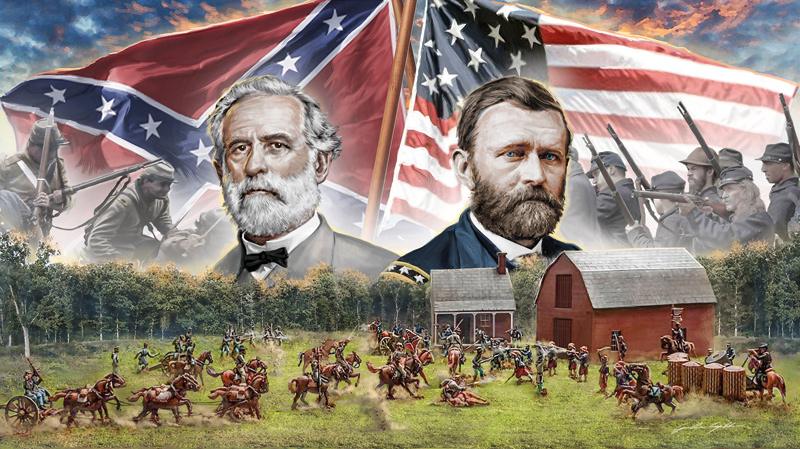

The Peninsula Campaign of 1862 showcased both the potential and limitations of Union strategy under General George McClellan. Despite having significant numerical advantages and better equipment, McClellan’s cautious approach allowed Confederate forces under Robert E. Lee to employ aggressive tactics that neutralized Union advantages. The Seven Days’ Battles demonstrated Lee’s willingness to accept heavy casualties in exchange for strategic initiative, a approach that would characterize Confederate strategy throughout much of the war.

The Battle of Antietam in September 1862 represented the war’s bloodiest single day and a crucial turning point in Union fortunes. McClellan’s discovery of Lee’s battle plans gave the Union army an unprecedented opportunity to destroy the Confederate forces, but cautious execution allowed Lee to escape with his army intact. Despite the tactical disappointment, the strategic victory provided President Lincoln with the political cover to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, transforming the war’s moral dimensions.

The Gettysburg Campaign of 1863 marked the high-water mark of Confederate hopes for military victory and foreign recognition. Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania represented a calculated gamble to shift the war’s focus away from Virginia while potentially influencing Northern public opinion. The three-day battle at Gettysburg, from July 1-3, 1863, became the war’s largest engagement and demonstrated how improved artillery and defensive positions had shifted the tactical balance against offensive operations.

Ulysses S. Grant’s assumption of overall Union command in 1864 brought a new strategic approach that emphasized coordinated pressure across multiple theaters. The Overland Campaign, while costly in casualties, demonstrated Grant’s willingness to sustain offensive operations despite tactical setbacks. Meanwhile, William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign and subsequent March to the Sea showed how Union forces could destroy the