The Influence of the Printing Press on the Renaissance and Reformation

Introduction: A Technological Revolution Ignites Change

The invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century stands as a pivotal moment in human history, a technological leap that irrevocably altered the course of Western civilization. Before Johannes Gutenberg’s revolutionary innovation around 1450, the painstaking process of hand-copying manuscripts severely limited the availability of written material. Books were expensive, rare, and often riddled with errors. Gutenberg’s press, employing movable type and a refined printing process, dramatically changed this. It facilitated the mass production of books, pamphlets, and other printed materials, making knowledge accessible to a vastly wider audience than ever before. This democratization of knowledge directly fueled the intellectual ferment of the Renaissance and the seismic theological shifts of the Reformation, transforming both movements in profound and lasting ways. This essay will explore the multifaceted impact of the printing press on these transformative periods, examining its influence on the dissemination of ideas, the rise of literacy, the evolution of education, and the overall cultural and intellectual landscape of Europe.

The Renaissance: A Rebirth Fueled by Accessible Knowledge

The Renaissance, a period of flourishing artistic, literary, and intellectual achievement spanning roughly from the 14th to the 17th centuries, witnessed a revival of interest in classical Greek and Roman learning. This “rebirth” was not solely a matter of rediscovering ancient texts; it was also a process of reinterpreting and applying those texts to contemporary concerns. The printing press played a crucial role in facilitating this revival by making classical texts readily available. Before the press, access to classical works was largely confined to monastic libraries and the courts of wealthy patrons. The painstaking process of hand-copying meant that few copies existed, making scholarly study a privilege of the elite.

Gutenberg’s press dramatically altered this scenario. The ability to rapidly produce multiple copies of texts meant that scholars and students alike could access previously inaccessible works of literature, philosophy, science, and history. The works of Aristotle, Plato, Cicero, and other classical authors became more widely studied, enriching the intellectual discourse of the Renaissance. This increased access fostered a new wave of intellectual curiosity and debate, leading to advancements in various fields.

Furthermore, the printing press facilitated the spread of humanist ideas. Humanism, a dominant intellectual movement of the Renaissance, emphasized human potential and the importance of education, reason, and individual achievement. Humanist scholars, such as Petrarch and Erasmus, utilized the printing press to disseminate their ideas and writings. Their works, which often focused on classical texts and their application to human life, quickly spread throughout Europe. The printing press ensured that humanist philosophies were not confined to a select group of scholars but reached a broader audience, profoundly shaping the cultural and intellectual climate of the age.

The impact on art and literature was equally significant. The printing press allowed for the widespread dissemination of artistic techniques and literary styles. Woodcuts and engravings, previously rare and costly, could now be reproduced in large numbers, allowing artists to share their work and influencing artistic styles across geographical boundaries. Similarly, the printing of poetry, plays, and novels helped to establish new literary forms and fostered a burgeoning literary culture. The increased accessibility of books led to a greater demand for them, stimulating a growth in the publishing industry and generating further innovation in printing techniques.

The Reformation: A Religious Revolution Accelerated by Print

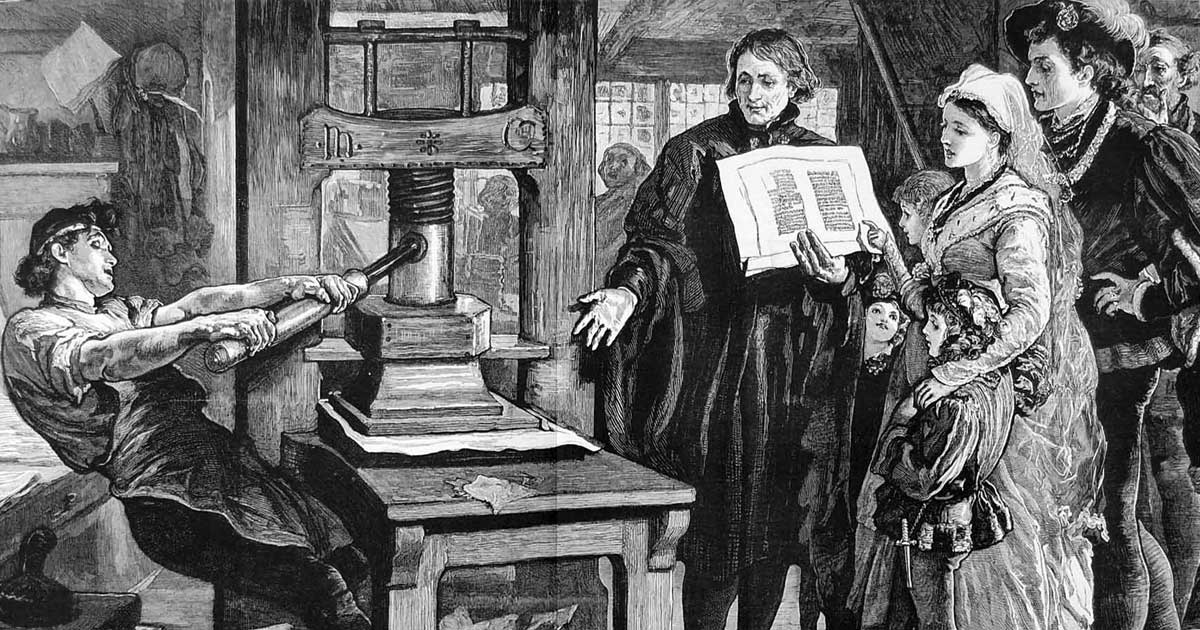

The Protestant Reformation, which began in the early 16th century with Martin Luther’s challenge to the authority of the Catholic Church, was another watershed moment profoundly shaped by the printing press. Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses, his famous critique of the Catholic Church’s practice of selling indulgences, was swiftly translated into various vernacular languages and disseminated throughout Europe, thanks to the printing press. Before this, such a widespread and rapid dissemination of religious critique would have been impossible.

The printing press became Luther’s most powerful weapon in his fight against the established church. He used it not only to publish his own works but also to encourage the translation and publication of the Bible into vernacular languages. This move challenged the Church’s control over the interpretation of scripture and empowered individuals to engage directly with religious texts. The ability of ordinary people to read and interpret the Bible themselves was revolutionary, undermining the Church’s monopoly on religious authority.

Other reformers, such as John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli, also used the printing press to spread their ideas and challenge the Catholic Church. The resulting flood of pamphlets, tracts, and theological treatises sparked heated religious debates and contributed to the fragmentation of Christendom. The speed and scale of the Reformation’s spread were largely due to the printing press’s ability to rapidly produce and disseminate religious materials. This facilitated the formation of new religious communities and contributed to the rise of Protestantism across Europe. The printing press not only facilitated the theological debates but also allowed reformers to engage in public relations campaigns, creating a more informed and engaged public sphere.

The Spread of Knowledge and Ideas: Breaking Down Barriers

Prior to the printing press, the dissemination of knowledge was heavily reliant on the slow and often inaccurate process of hand-copying. This made knowledge a privilege of the wealthy and powerful, effectively creating a knowledge barrier. The printing press shattered this barrier. The ability to produce multiple copies of books and other documents quickly and efficiently made knowledge far more accessible, facilitating a significant rise in literacy rates. This broadened access fueled intellectual curiosity and encouraged wider participation in scholarly debates and discussions.

The printing press also transcended geographical and linguistic barriers. The ability to print in multiple languages meant that ideas could travel across national and cultural borders, fostering a more interconnected intellectual community. The exchange of information and perspectives accelerated, leading to the cross-pollination of ideas and the development of a more cosmopolitan intellectual landscape. The rapid spread of scientific discoveries, literary works, and philosophical treatises fostered innovation and progress in various fields. The printing press democratized knowledge, placing power in the hands of more people, promoting literacy, and fostering innovation.

The Impact on Education and Literacy: A More Informed Society

The printing press significantly influenced the evolution of education and literacy. The mass production of books and educational materials made learning more accessible. Previously expensive texts became more affordable and widely available, driving up literacy rates across Europe. The increased demand for teachers and educational institutions followed this surge in literacy, fostering the development of new schools and universities.

The rise in literacy had profound social and political implications. A more educated populace could engage more meaningfully with public affairs, influencing political and social discourse. This increased participation contributed to a more active and informed citizenry. The printing press itself became a tool for education, leading to the creation of primers and educational texts that standardized the learning process. The standardization of language and the availability of texts also fostered a greater sense of cultural unity across Europe.

The Enduring Legacy: A Continuing Influence

The invention of the printing press marked a profound turning point in human history, and its legacy continues to resonate in the modern age. Its impact on the Renaissance and Reformation cannot be overstated. It democratized knowledge, fueled intellectual revolutions, and fundamentally changed the way information was created, disseminated, and consumed. While the digital age has ushered in new methods of communication and information dissemination, the fundamental principles of the printing press – mass production, accessibility, and the democratization of information – remain cornerstones of our modern world. The printing press’s influence continues to shape our understanding of knowledge, education, communication, and the power of technology to transform societies. The ease of access to information, whether it was a religious tract or a scientific treatise, fostered debate, spurred innovation, and fundamentally altered the course of human history. The printing press’s impact serves as a powerful reminder of the transformative power of technology and its ability to shape both the cultural and intellectual landscape.