The History of the Reformation and the Protestant Church

The Protestant Reformation, a pivotal event in Christian history, irrevocably altered the course of Western civilization. This complex and multifaceted movement, unfolding primarily during the 16th century, was spearheaded by individuals like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli. Their efforts to reform the Catholic Church ultimately resulted in the birth of Protestantism, fracturing the religious unity of Europe and leaving an enduring legacy on theology, politics, and culture. This exploration delves into the intricate details of the Reformation, examining its historical context, key figures, theological debates, and profound societal impact, providing a comprehensive understanding of its enduring significance.

I. The Seeds of Discontent: Contextualizing the Reformation

The Protestant Reformation wasn’t a spontaneous eruption; it was the culmination of centuries of simmering discontent, fueled by a confluence of theological, social, political, and economic factors. The Catholic Church, the dominant religious force in Western Europe for over a millennium, had accumulated considerable power and wealth, but simultaneously suffered from internal weaknesses that contributed to its eventual challenge.

A. The Corruptions within the Church: By the 16th century, widespread criticism targeted the Church’s perceived moral and doctrinal failings. The sale of indulgences, certificates purportedly absolving individuals from temporal punishment for sins, had become a lucrative, albeit morally questionable, practice. The sheer scale of this practice, coupled with its blatant commercialization, fueled public outrage and resentment. The lavish lifestyles of many church officials contrasted starkly with the poverty and hardship experienced by the majority of the population, further exacerbating public discontent. Nepotism and simony (the buying and selling of church offices) were also prevalent, eroding public trust and respect for the Church’s hierarchy.

B. The Rise of Humanism and Renaissance Scholarship: The intellectual ferment of the Renaissance and the humanist movement played a significant role in preparing the ground for the Reformation. Humanists emphasized the importance of classical learning and a return to the original sources of Christian thought. This emphasis on critical examination and independent scholarship encouraged a renewed interest in the Bible, prompting individuals to question the Church’s interpretations and authority. Figures like Erasmus of Rotterdam, while not a Protestant reformer himself, played a vital role in promoting biblical scholarship and translating the New Testament into Greek, paving the way for a deeper understanding and independent interpretation of scripture.

C. Socio-Economic Transformations in Europe: The burgeoning urban centers of Europe, with their expanding merchant classes and artisan guilds, presented a challenge to the Church’s feudal and hierarchical structures. These newly affluent groups often sought greater autonomy and were less inclined to accept the Church’s traditional authority unquestioningly. Moreover, the devastating impact of the Black Death in the 14th century profoundly impacted the population’s faith. The Church’s inability to fully explain or alleviate the suffering caused by the plague led to a widespread questioning of its power and efficacy. This erosion of faith created a fertile ground for dissenting voices and alternative interpretations of religious doctrine.

D. Political Fragmentation and National Identities: The political landscape of Europe was increasingly fragmented, with powerful monarchs and emerging national identities challenging the universal authority of the Pope. Kings and princes often resented the Church’s influence on their territories and the significant portion of their resources that flowed to Rome. This political tension created opportunities for reformers who could align themselves with powerful rulers seeking to enhance their own authority at the expense of the Papacy.

II. The Architects of Change: Key Figures of the Reformation

Several charismatic and influential figures propelled the Reformation forward, each contributing uniquely to its trajectory and theological development.

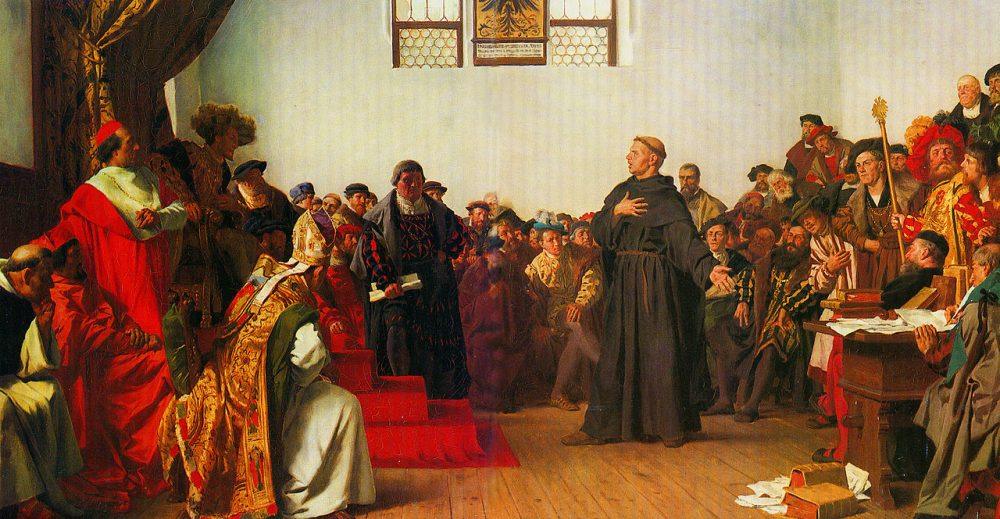

A. Martin Luther (1483-1546): Often considered the catalyst of the Reformation, Luther was a German Augustinian monk and theologian whose critique of indulgences ignited the movement. His Ninety-Five Theses, famously nailed to the church door in Wittenberg in 1517, challenged the very foundation of the Church’s authority on salvation. Luther’s emphasis on “sola scriptura” (scripture alone) as the ultimate authority, “sola fide” (faith alone) as the means of salvation, and “sola gratia” (grace alone) as the source of salvation, fundamentally challenged traditional Catholic doctrine. His translation of the Bible into German empowered ordinary people to access and interpret scripture independently, further undermining the Church’s monopoly on religious knowledge. Luther’s strong personality and unwavering conviction, despite facing excommunication and the threat of imperial punishment, made him a powerful symbol of defiance and a rallying point for those seeking religious reform.

B. John Calvin (1509-1564): A French theologian, Calvin significantly shaped the development of Reformed Protestantism. His “Institutes of the Christian Religion,” published in 1536, presented a systematic and comprehensive theological framework, emphasizing God’s sovereignty, predestination, and the importance of a disciplined life. Calvin’s influence extended beyond theology; he established a theocratic government in Geneva, Switzerland, creating a model for other Reformed communities. His emphasis on hard work, thrift, and social responsibility, often described as the “Protestant work ethic,” had a profound impact on the economic and social development of many Protestant societies.

C. Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531): A Swiss reformer, Zwingli’s ideas largely paralleled Luther’s, emphasizing the authority of scripture and the priesthood of all believers. However, Zwingli differed from Luther on the interpretation of the Eucharist (Lord’s Supper), advocating for a symbolic understanding rather than Luther’s belief in the real presence of Christ in the sacrament. This difference led to significant theological debates and divisions within the burgeoning Protestant movement. Zwingli’s influence was primarily confined to Switzerland, where his reforms led to the establishment of a distinct Reformed tradition.

III. Theological Battles: Central Debates of the Reformation

The Reformation was characterized by intense theological debates that fundamentally reshaped Christian doctrine and practice.

A. Justification by Faith Alone: The central tenet of the Reformation was the doctrine of “sola fide,” or justification by faith alone. Luther and other reformers argued that salvation was a free gift of God’s grace, received through faith in Jesus Christ, and not earned through good works or adherence to Church rituals. This directly contradicted the Catholic Church’s teaching on salvation, which emphasized both faith and good works. This fundamental difference remains a key point of distinction between Protestant and Catholic theology.

B. The Authority of Scripture: The reformers championed “sola scriptura,” asserting the Bible as the ultimate authority in matters of faith and practice. They rejected the Church’s traditions and papal pronouncements as sources of equal or greater authority than scripture. This emphasis on biblical authority spurred the translation of the Bible into vernacular languages, making it accessible to a wider audience and empowering individuals to interpret scripture independently.

C. The Nature of the Sacraments: The reformers challenged the Catholic Church’s understanding of the sacraments. While retaining baptism and the Lord’s Supper, they rejected the transubstantiation doctrine (the belief that the bread and wine literally transform into the body and blood of Christ) and other sacraments like confession, penance, and extreme unction. The interpretation and significance of the sacraments became a major point of contention among different Protestant groups.

D. The Priesthood of All Believers: Rejecting the hierarchical structure of the Catholic Church, the reformers advocated for the “priesthood of all believers,” arguing that all Christians have direct access to God through faith in Christ and do not require the mediation of priests or other clergy. This concept fundamentally democratized the Christian faith, empowering individuals to participate actively in their own spiritual lives.

IV. The Ripple Effect: Societal Impact of the Reformation

The Reformation’s impact extended far beyond religious doctrine, profoundly shaping Western society and culture.

A. The Rise of Literacy and Education: The emphasis on “sola scriptura” fueled a surge in literacy as people sought to read the Bible in their own languages. The establishment of Protestant schools and universities further enhanced educational opportunities, contributing to a more literate and educated populace. This increased literacy played a pivotal role in the development of modern societies.

B. Political and Social Change: The Reformation challenged traditional political structures and fostered the development of national identities. The decline of papal authority weakened the centralized power of the Church, contributing to a more fragmented and decentralized political landscape. The concept of the “priesthood of all believers” promoted a sense of individual autonomy and responsibility, laying the groundwork for more democratic and egalitarian societies.

C. Economic and Social Transformations: The “Protestant work ethic,” emphasizing hard work, frugality, and diligence as signs of God’s grace, contributed to the rise of capitalism and economic development in many Protestant regions. This work ethic encouraged innovation, entrepreneurship, and the accumulation of wealth, contributing to significant economic transformations. Furthermore, the rejection of monasticism and the redistribution of Church lands reshaped social structures, contributing to the rise of a more secularized society.

D. Artistic and Cultural Shifts: The Reformation led to significant changes in art and culture. The rejection of religious imagery and the destruction of religious art in some Protestant regions had a profound impact on artistic expression. However, Protestant hymnody flourished, creating rich musical traditions that continue to this day. The emphasis on vernacular languages also influenced literature and the development of national languages.

V. A Lasting Legacy: The Enduring Influence of the Reformation

The Reformation’s legacy continues to resonate across the globe, shaping Christian theology, political structures, and cultural norms.

A. The Rise of Protestant Denominations: The Reformation did not produce a single unified Protestant church; instead, a multitude of denominations emerged, reflecting differing interpretations of scripture and theological perspectives. These denominations, including Lutheranism, Calvinism, Anglicanism, and various Anabaptist groups, developed their own unique theological traditions, worship practices, and church structures.

B. Religious Wars and Political Conflicts: The religious divisions sparked by the Reformation led to decades of religious wars and political conflicts across Europe. The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), one of the most devastating conflicts in European history, serves as a stark reminder of the profound impact of the Reformation on the political landscape. These conflicts shaped the map of Europe and influenced the development of international relations for centuries.

C. The Development of Modernity: The Reformation played a significant role in the development of modernity. The emphasis on individual conscience, religious toleration (though often unevenly applied), and the separation of church and state paved the way for more secular and pluralistic societies. The Reformation’s emphasis on individual responsibility and critical thinking contributed to the growth of scientific inquiry and the Enlightenment.

Conclusion:

The Protestant Reformation, a multifaceted movement driven by theological conviction and fueled by broader societal forces, profoundly reshaped Western civilization. Its legacy is complex and multifaceted, encompassing theological innovation, political upheaval, social transformation, and enduring cultural influences. While the religious wars and divisions it sparked were devastating, the Reformation also fostered a greater emphasis on individual conscience, education, and a more direct relationship with the divine. The Reformation’s lasting impact on theology, politics, and culture continues to be felt in the world today, reminding us of the enduring power of ideas to shape the course of history. Understanding the Reformation offers valuable insight not only into the history of Christianity but also into the broader dynamics of social and political change.